By Susanna Eastburn, Chief Executive, Sound and Music

A version of this blog also appeared in the Guardian on the 8 March 2019.

Two years ago today, Sound and Music (the UK’s national organisation for new music) made a public pledge to achieve gender equality across all of our work with composers and artists, under the headline “50:50 by 2020”. Anniversaries are an opportunity to reflect, and this one has not only led me to think about the headway we’ve made – but also the very significant and systemic challenges that remain.

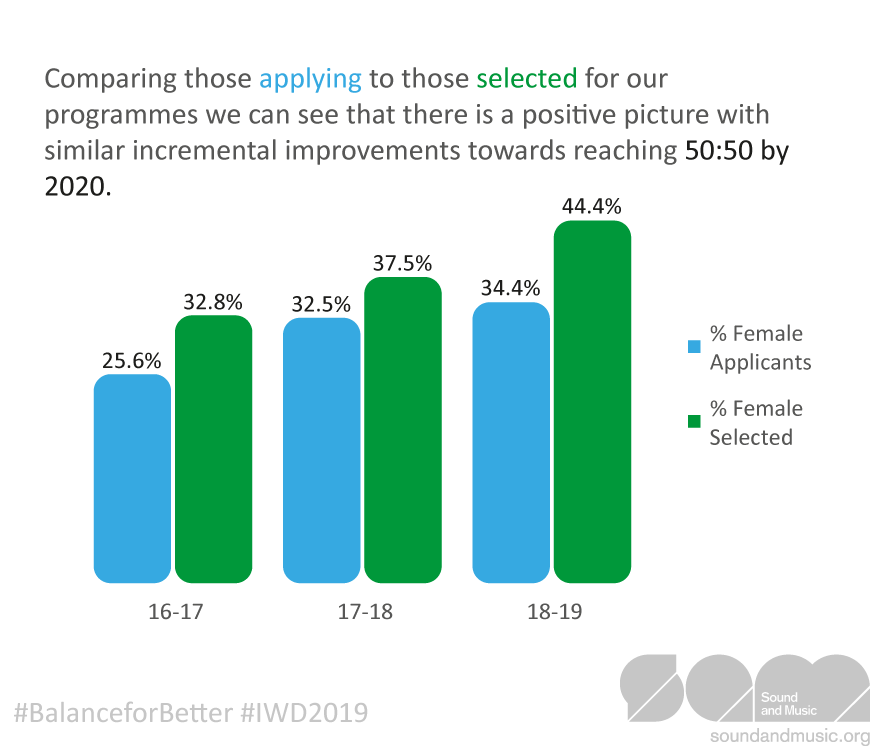

At one level, we’ve made good progress. This year, 44.5% of composers Sound and Music are working with identify as women, as opposed to 32.8% two years ago. To reassure all those who said that we were sacrificing considerations of artistic quality on the altar of tokenism, this has been artistically thrilling not only for us, but for everybody involved – the composers themselves but also our partner organisations and indeed audiences. It turns out that working with a wider range of composers and being interested in what they have to say leads to a greater variety of work, more distinctive programming and a very appealing energy. I see great examples of this across the sector, such as the recent SoundState Festival at the Southbank Centre which had as its featured artists the composers Du Yun and Rebecca Saunders, and the flautist Claire Chase, and was buzzing with people and ideas for its entire duration.

However our statistics also reveal that only 34% of applications to our programmes come from those who identify as women despite all our work to change perceptions about who can be a composer, and despite all of our very public commitments and comments on the subject. And I suspect that the percentage of female applicants to most other schemes across the sector is even lower. We’re still one of the very few organisations in the UK to release our data publicly.

One of the many arguments posed against gender balance (not only in music) is about the consistently lower percentage of applications from women in any competitive application process. At some point between education (where the balance is more equal: indeed more girls than boys are now taking GCSE music) and a professional career, many women drop off, lose heart and stop putting themselves forwards altogether.

One of the many arguments posed against gender balance (not only in music) is about the consistently lower percentage of applications from women in any competitive application process. At some point between education (where the balance is more equal: indeed more girls than boys are now taking GCSE music) and a professional career, many women drop off, lose heart and stop putting themselves forwards altogether.

Why is this? Where are composers who happen to be women discouraged and by who or what? What are the barriers to becoming a professional composer and do these affect one gender more than another?

Many of the answers to these questions, of course, are about wider society: about how women are portrayed in the media, about the weight of childcare and domestic arrangements disproportionately borne by women, about women being conditioned so often from a young age to ‘be nice’, ‘stop showing off’, leaving an embedded belief that shame, chastisement or punishment would follow any bold foray. (I speak as somebody who was once told by an older male mentor that I could “come over as rather aggressive” after disagreeing with him.)

This plays out in the world of music, however, in many different ways. Some are more obvious, such as the young black composer who was told that she “didn’t look like a composer” in her first year at conservatoire, or the established figure told that she couldn’t have written her large orchestral piece “without help”.

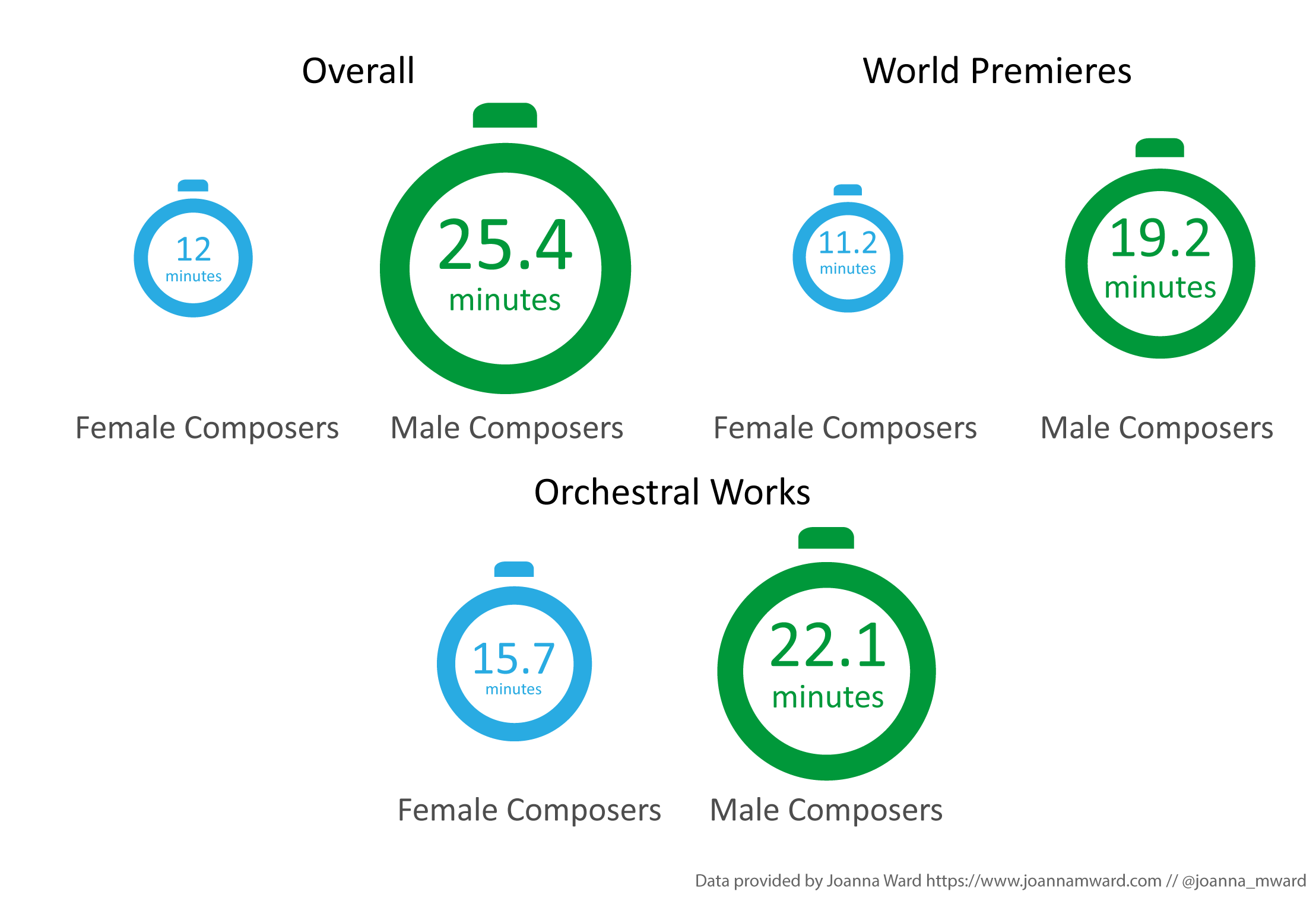

However there is a more subtle edge to how composers who are women are treated. I’ve been talking recently to the brilliant young composer Joanna Ward, who for her dissertation has been researching gender equality in the field of composers. Part of her research has been to look at the programming of the BBC Proms 2013-18. The number of women being commissioned and programmed by the Proms is improving; however what her research reveals is that women take up disproportionately less time in the programme. The average duration of a woman’s piece was 12.0 minutes, and the average duration of a man’s piece was 25.4 minutes. Even among world premieres (in other words, the Proms’ own commissions) the average duration of a world premiere by a woman was 11.2 minutes and the average duration of a world premiere by a man was 19.2 minutes. And looking specifically at orchestral pieces, the average duration of an orchestral piece by a woman was 15.7 minutes, whilst that of a man was 22.1 minutes.

In some ways it is unfair to single out the Proms in this. Their commitment to gender equality in commissioning as a result of PRS Foundation’s Keychange initiative is laudable, and their data is more readily available than many others. (I suspect that other series and festivals would be no better and in many cases much worse.) And what the data doesn’t tell you is how this striking disparity has arisen. Are men being commissioned to write longer pieces? Are women more likely to compose shorter pieces? If so, why?

In some ways it is unfair to single out the Proms in this. Their commitment to gender equality in commissioning as a result of PRS Foundation’s Keychange initiative is laudable, and their data is more readily available than many others. (I suspect that other series and festivals would be no better and in many cases much worse.) And what the data doesn’t tell you is how this striking disparity has arisen. Are men being commissioned to write longer pieces? Are women more likely to compose shorter pieces? If so, why?

However it is a stark illustration that as an aspiring composer, if you are a woman you will be looking at a future where, even if you’re lucky enough to avoid overtly sexist comments and behaviour, it seems likely that you will be taken less seriously, and allowed to take up less space, than your male colleagues.

Targets are important. In my own organisation, I’ve seen how they can bring transparency and focus, and drive positive change. But achieving true gender equality in the music world will require us to go far beyond targets and take a long hard look at how we operate as a sector, including questioning our unconscious assumptions about what women are capable of.

At a time when the power of art to connect and move us feels more important than ever, this feels not only essential, but a tremendous creative opportunity.

If you’d like to support Sound and Music’s work to champion new music and the work of all British composers and creators you can do so here.